The choice to use the vague language of the old European Union spirit definitions caught many off guard. There had been a ton of work undertaken by people in the industry to better codify the term. As late as 2017, The Gin Guild was undertaking research to better understand what “predominant” even means.

However, when the much awaited draft of the new European Union spirit regulations went out for public comment in 2019, surprisingly the word “predominant” remained. And with it, all of the vagary regarding the term.

Full transparency: I am a member of the Gin Guild and was consulted by both European and American regulators as they studied what “predominant” means. This represents my opinion on the topic and does not represent the opinions or points of view of any other parties.

The Problem with Predominance

To put it simply, it means nothing. Less than nothing. It is purely subjective and purely about taste perception.

Thus far, most of our academic research suggests that taste and flavor perception varies from person to person— and the number of variables which influence perception are sufficient that we can broadly simplify it and call taste subjective.

While sensory scientists, especially in the wine field, have aimed to create vocabularies and rubrics to make flavor analysis more consistent (this is what we did too when we developed our flavor diagram). These frameworks are effective in critiques and professional circles, but are generally not sufficient to constitute a legal framework.

In other words, the flavor analysis of an expert tasting something generally doesn’t meet the high bar for revoking someone’s livelihood as a gin distiller. Measurable and quantifiable metrics for categorizing products is preferred. Otherwise, subjective measures generally rely on demonstrating intent (intent to mislead). If a distiller truly believes the juniper is predominant in her gin— whose to say it’s not a gin?

In short, anyone hoping for more teeth in flavor-based regulations to tighten up what is allowed to be a gin, are going to be disappointed. Furthermore, the proliferation of vague taste based language in the new law suggests that we’re moving in the opposite direction.

Predominant is predominant in E.U. Regulation 2019/787

The use of the word “predominant” appears in the new European Union spirit definitions 14 times (up from ten times in the 2008 law).

| Spirit | # of “predominant” | Notes |

| Vodka | 4 | Predominant “flavor” for flavored vodka |

| Gin | 2 | “in the presence of juniper berries and of other natural botanicals, provided that the juniper taste is predominant.” |

| Kummel | 1 | Flavoring preparations may be used to achieve flavor |

| Anisette | 1 | Added in 2019. |

| Bitter tasting drink | 1 | |

| Pacharán | 1 | New category in 2019 |

| Liqueurs and Cremes (generally) | 2 | |

| Spritglögg | 1 |

Other spirit categories have alternative wording for similar concepts. For example, Aquavit is defined as, “but the flavor of these drinks shall be largely attributable to distillates of caraway or dill.”

Juniper flavored spirit drink, gin’s lower ABV sister defines flavor as “a combination thereof may be used in addition to juniper berries, but the organoleptic characteristics of juniper shall be discernible, even if they are sometimes attenuated“.

Anisette specifies its flavor clause in this way: “Other natural plant extracts or aromatic seed may also be used, but the aniseed taste shall remain predominant.“

Measuring flavor with science.

It is technically possible to evaluate flavor using laboratory apparatus. Some distilleries like Laverstoke Mill (home of Bombay Sapphire) use Gas Chromotography to identify volatiles in their gin.

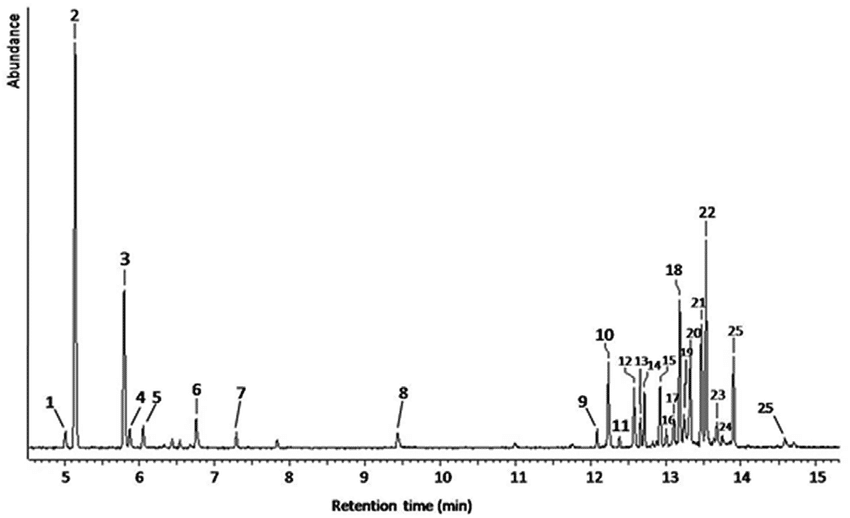

In short, Gas Chromotagraphy works by taking a small sample of a liquid and heating it until it vaporizes. A carrier gas takes the volatile gases to a detector. The detector then measures the amount of volatiles that are present and represents them on a two dimensional chart. The y-axis represents the quantity of a given molecule; the x-axis represents time. This diagram is called a GC-MS chromatogram and broadly represents a “fingerprint” of the sample which was used.

The molecules on the left of the diagram evaporate more readily and have lower boiling points. This is one of the ways scientists can identify which compounds are present.

For example, alpha-pinene is a light molecule that volatilizes readily. It can be seen as peak “2” in the diagram below. Each molecule which is able to be identified is assigned a number.

As we know alpha-pinene tastes and smells a bit like conifers, we can broadly infer that the essential oil below may taste somewhat ‘piney.’

This is a very simplistic explanation. If you want to dig in more deeply, Thought Co has a great overview of the science, procedure and mechanisms behind using Gas Chromatography.

They can compare the results of a new run against a standard-bearer. The job of tasting and quality control is often still the job of a master distiller; however, technology has afforded distillers another tool for ensuring consistency across batches.

The future of defining flavor in law

Although the cost of this kind of lab work has declined dramatically in the last twenty years, it may still be too expensive for regulatory agencies to apply and too onerous for distillers without labs to design new products that meet a chromatogram requirement.

But it is technically feasible.

In my opinion, this is the very likely future of spirit categorization and identification.

In short, it’s surprising that more concrete steps weren’t taken to address the “predominant” flavor problem in the 2019 regulations. To me, it’s surprising that rather than cultivating new, more descriptive language that other spirit categories latched on to the vague language that has been so problematic for the gin category.

Until some numerical measures are added to the law, it remains subjective and largely symbolic. As of 2020, the key takeaway is that nothing has changed in terms of the flavor of London Dry Gin is defined.