Page 79 of Jerry Thomas’s seminal 1862 work How to Mix Drinks, Or the Bon Vivant’s Companion has always stood out to me. While many of the drinks in his book still seem current and are made today, these three stick out as relics of spirits and gin’s distant past.

Thomas himself seems keenly aware of this as well. He adds, “the above three drinks are not much used except in country villages,” slyly implying that even in 1862 these drinks are backwards concoctions, sipped by the those non-urbane types.

Despite its myriad reprints and contemporary interpretations, these three drinks tend to be glossed over. However, I think its high time that these cocktails get a closer look. What are they? Who was drinking them? And why would Jerry Thomas include them?

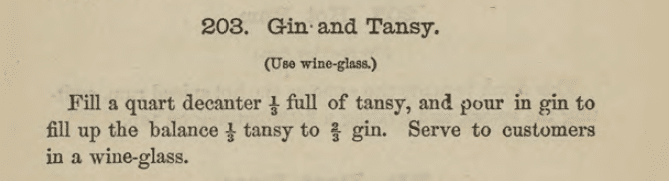

Gin and Tansy

Today, the Tansy is best known as an invasive perennial weed. It grows to about three feet in height with clusters of yellow, globe shaped flowers. But it once was an important part of European culinary tradition.

Tansy was an essential plant in early Renaissance gardens in England. Mayster Jon Gardener included it in his ~1350 book The Feate of Gardening. Tansy had a dual purpose. Firstly, it’s flavor which is described as something like a camphorous rosemary was used to flavor meats and puddings. Secondly, it was included in lists of herbs for distillation, implying a medicinal use.

The plant’s medicinal use goes back perhaps as far as the Greeks. It’s reputed properties span the gamut from measles, inducing abortion, and a mere upset stomach. As quaint as these distant herbal remedies may seem, in Thomas’s time Tansy was still fairly common in pharmacoepias and other medicinal literature.

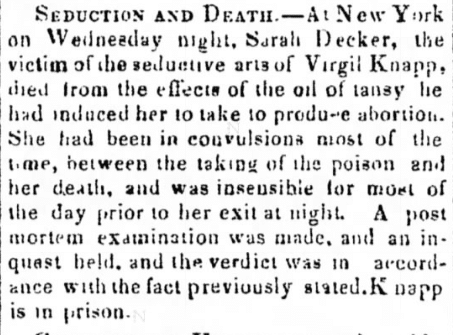

The New Family Herbal, published in 1863 says “The decoction of Tansy, or the juice drank in wine, promotes urine, curses strangury, and strengthens the kidneys.” In an 1861 Welsh pharamacoepia, the juice of tansy in old ale is prescribed for a persistant stomach ache. However, the New York Journal of Medicine in 1861 included a story about Tansy that matches our current understanding of the herb— a young woman died from drinking tansy tea. Cause of death? Poisoning.

This brings us back to Jerry Thomas’s infamous cocktail. In those ratios as written, this drink approaches the toxic threshold. A mere 4 mL of Tansy essential oil is all it takes to kill an adult human. Despite this, Tansy is safe in distilled spirits. It’s even purported to be among the ingredients in Chartreuse.

Despite the fact that Tansy was known to be toxic in the 19th century, it still had a place in bars. A.J. Baine in his book Big Shots, The Men Behind the Booze he tells the story of Jack Daniel (yes, THE Jack Daniel, of whiskey renown) was known to mix a julep with his whiskey— instead of mint though, he used Tansy. While Jack’s variation seems unusual today, hints lie in the work of Samuel Griswold Goodrich that it might not be as novel as it seems, as well as hinting at what Thomas might have meant by the “country.”

“In the Southern States, where the ague is so common and troublesome a malady…it has grown into a custom to fortify the body from attacks of the disease by means of juleps. [..] the julep is made by breaking into the raw liquor a sprig of tansey, or several kinds of mint. […] At the hotels of New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore, mint juleps which were first introduced from the South and West are now furnished to all who call for them. They consist of spirits, sugar, and mint with small pieces of ice.” —A Pictorial Geography of the World (1810).

Julep did have a more general definition at the time, broadly a spirit mixed with sugar and other medicinal herbs— but the Tansy Julep recurs in Southern Newspapers. In a January 1859 edition of the Alexandria Post a Virginia Merchant editorialized about changing times and recounted a time “When I could call for Tansey Julep before breakfast.”

While tansy was nearly unheard of in bars in the Northern United States, in the South, the ‘Tansy Julep’ was still enough of a thing in some pockets that a bartender may have had some ready in the chance someone might have requested one. The presence of Tansy in some Southern versions of the Julep may have been the result of cost and convenience. The same qualities that make tansy an invasive weed in much of the world led to its wide and easy availability. While mint would have been cultivated in a garden, tansy might have grown of its own accord in disturbed soils at the edges of a plantation.

Northern papers that mentioned tansy were more likely to focus on the ill effects of it. Accidental death and (even murder) weren’t uncommon.

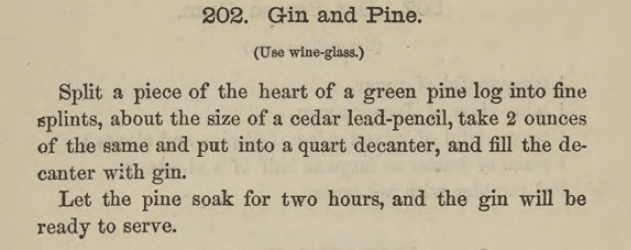

Gin and Pine

Pine bark and pine bark flour were starvation foods in Northern Europe. In times of bad harvest, people would make pine bark bread. Surprisingly, it’s quite nutritious, albeit not great tasting.

This drink seems mysterious to us today— what bar has green pine log macerations on hand? But what’s really fascinating was that even in Jerry Thomas’s time this drink was something of a mystery.

“I was a guest at Appledore and felt considerably under the weather. [..] A friend of many years whispered in my ear, “Try gin and pine.” It was a mysterious proposition and I looked to him for an explanation.” Boston Evening Transcript, July 20th 1874.

Ben P. Shillabar was led downstairs to try the beverage. The bartender made it clear that that this was to be taken as a medicine. It settled his stomach immediately and he wrote to the paper to extol its virtues as a medicine. He elaborates as well, perhaps shedding some light on the origins of this mysterious drink in Thomas’s book— “the article is the peculiar and exclusive property of the Appledore, and its origin dates very far back, probably to a time when the pines covered the island.”

Jerry Thomas began his career bartending in New England— not far from Kittery, Maine and the Appledore Hotel. The first mention of him as a bartender was as a twenty year old at a New Haven saloon. The Appledore Hotel opened in 1847 and had reputation as being a hub for artists. This was around the same time that Thomas left the east coast for San Francisco, so it’s unlikely that either Thomas has a hand in inventing the cocktail for the Appledore or that he heard about it after the Appledore was said to have invented it.

The cocktail’s origins are obscure, but the wording in Thomas’s book suggests that this was part of the oral tradition he was codifying as the recipe assumes a pine mono-culture. The intended recipient of this recipe would either know what was meant by “pine,” or would only be in a place where a single pine existed.

Otherwise, pine identification plays a part in re-creating this recipe. If the recipe he transcribed was part of the same oral tradition that the Appledore’s Gin and Pine was based on, it’s likely the White Pine that was used. The White Pine is widespread in that region and has a long history as a medicinal plant. The Native People’s in the White Pine’s natural range ate the inner bark of the plant as part of their diet.

Similar to Gin and Tansy, Gin and Pine suggests a regional appeal and a regional oral tradition. This time though, from the Northern United States.

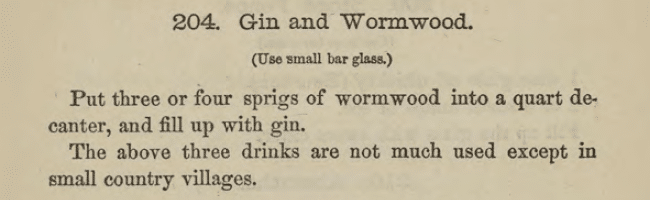

Gin and Wormwood

If you know wormwood, you already know— the recipe Jerry Thomas transcribed would be incredibly bitter.

Unsurprisingly, given it powerful aromatic profile, wormwood is nearly ubiquitous in Pharmacopoeias pre-20th century. The New Family Herbal (1863) includes tens of recipes for a myriad maladies using the herb. In Thomas’s time wormwood would be used for: gout, boils, ague, inflammation of the eyes, scurvy, upset stomach, epilepsy, jaundice, dropsy, worm infections, fevers and (my personal favorite) hypochondria.

Wormwood and Gin in particular appear frequently together, even in pre-cocktail era literature. Charles Tovey, writing at the same time as Thomas said that the most common wormwood bitters was a “simple preparation.. the green wormwood in gin,” and although he bemoans that fact that the people who used to drink it as a morning pick-me-up are dying, he notes that it “may even at this time be observed in the shelves in a publican’s bar.” It would have been drank as a purl. That is, the wormwood and gin bitters would be mixed into some warm beer.

Thomas doesn’t go into any further detail about the Gin and Wormwood; however, a bartender in parts of the world where that purl was once common would still be well advised to have a bottle of wormwood infused gin on the back bar.